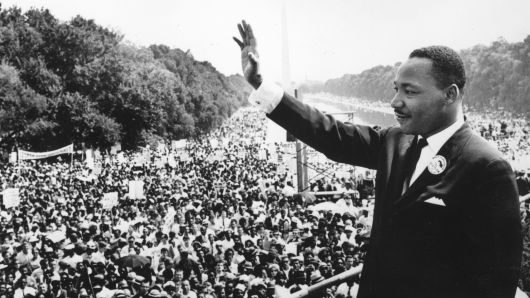

‘King’ of Change

Remembering the Legacy of an American Reformer

January 23, 2019

Even among the greatest of world leaders, Martin Luther King stands tall. He is the only non-president to get honored with his own national holiday, and he holds lasting influence on how African-Americans, and all peoples of the world, should be treated.

After the Civil War cleansed the most egregious of racial hierarchies imposed on African Americans, the institution of slavery, white Southerners began to immediately rebuild an institutionalised inequality—segregation. Before ever becoming de jure, organizations like the KKK and rhetoric like the “Lost Cause” inflamed tensions against African Americans, denying them voting rights and many economic freedoms.

After Plessy v. Ferguson wrote segregation into the law of the land, conditions only deteriorated. Black people got beaten up on the streets for drinking at “white” water fountains. “Black blood” and “white blood” were distinguished in the blood banks of WWII. Graveyards were segmented into “whites-only” or “blacks-only” zones.

By the 1950s, segregation had reached a breaking point. Racial de-segregation during WWII gave many black soldiers a taste of true freedom, only to be wisped away the moment they returned home. 100 years of Jim Crow led to a boiling kettle of popular resentment. Into this landscape of tectonic pressures came Dr. King, a young and restless Baptist preacher from Atlanta that embodied all the righteous fury of the black people of America.

What was shocking about King’s leadership was how he refused to sink to the level of the violence around him. When movements like the Black Panthers marched onto the streets with assault rifles, and the National Guard fumed clouds of tear gas over crowds of marchers, King’s nonviolence glowed like a beacon.

And King used that beacon to guide black and white alike to his ultimate dream—an America without the pervasive racial injustice that had characterized his childhood, defined his career and led to his untimely death by an assassin’s bullet.

The narrative of King’s legacy, and the larger narrative of civil rights today, is mostly a shoe-shined, sanitized story—He wanted racial equality, and he made a big important speech, “I Have A Dream”, and suddenly America was finally the bastion of equality it had long purported to be.

Yet a quick glance at the present reminds us that we stand not within the racial utopia dreamed by King, but instead a world where the average black person makes 70 cents to the white person’s dollar. We are not united by loving ties of brotherhood, but separated by rifts of misunderstanding anger. We have not risen about our hatred, but let it percolate and drone to a feverish tenor. King knew that one man alone could not heal the wounds of 400 years’ inequalities. But he worked for change nonetheless.

Because King knew life’s most unrelenting critical question to be: “What are you doing for others?” And through his legacy, he calls all of us to ask the same.