On Sept. 30, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 1780, legislation that banned non-profit private schools from admitting students based on donations or legacy. This policy notably affects schools such as Stanford, the University of Southern California, and Pitzer, whose currently admitted students comprise nearly one in every seven from legacy backgrounds.

Legacy, the practice of accepting students with family alumni, has been banned in public California schools since 1998 and in other private schools, such as Caltech, which has never practiced legacy, and Pomona which ended theirs in 2017.

“Giving preferential treatment to legacy applicants is a way the college can demonstrate loyalty to that alumni member [and] possibly secure future donations,” said Frank Smith, Director of College Counseling. “This factor can protect the college’s yield percentage, which is the number of admitted students who enroll. Schools like to report a higher yield percentage.”

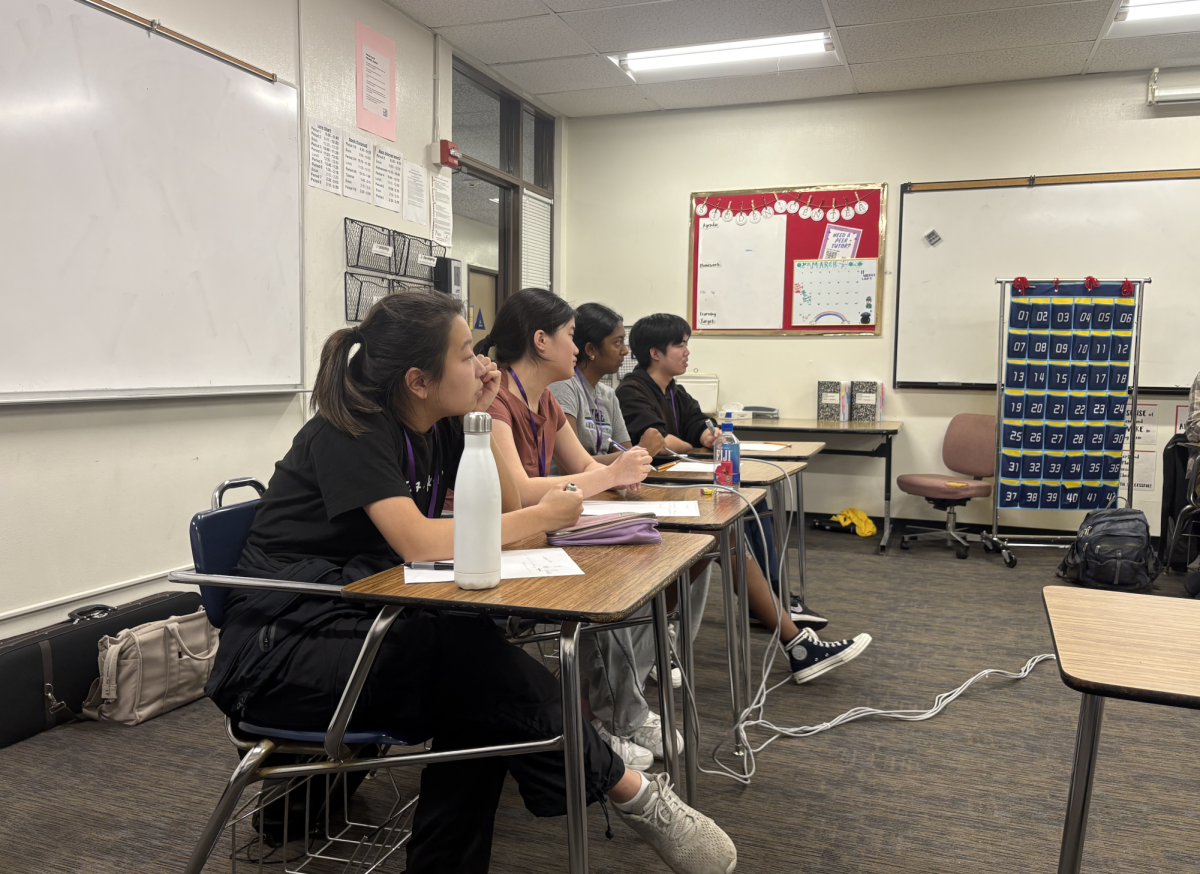

Although it remains unclear how AB 1780 will impact prospective college applicants starting in 2025, many students at Sage Hill seem to have a positive view of the new bill.

“[Legacy] can be unfair toward generationally low-income people or first [generation] students,” junior Jayla Chan said.

“Opponents [of legacy admissions] argue that the legacy system stymies efforts to diversify a student body with regard to race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, religion, etc.,” Smith said. “It denies access to students who have been historically underrepresented in higher education or been admitted to that institution at far lower numbers.”

Universities that consider legacy status reported 59% of their enrolled students identified as white, 12% as Hispanic, and 11% as Black, according to the Institute for Higher Education Policy. Institutions that avoid this preference were more diverse, reporting 51%, 15%, and 14% respectively for these reported student ethnicities. This data suggests that legacy families usually come from a generation of certain racial backgrounds. With admissions through familial connections, this data may not change without an amendment to the policy.

Junior Sarah Huang said the legacy admissions ban would “help level the playing field for students” at selective colleges, but was also concerned that a possible decline in donations from legacy families could affect colleges’ funding for scholarships and other endowments.

Smith anticipates college alumni will have a mixed response to this new regulation.

“I believe some alumni will be disappointed that legacy status will no longer be a factor at their alma mater, and it could impact their level of giving and support,” he said. “Others will appreciate the greater goal of opening spots for a wider range of applicants and accept the change as a necessary step.”

An example of alumni support towards the legacy ban would be the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which has not considered legacy status since 2006. In 2021, MIT received $89.8 million from 36,165 donors, many of whom were alumni.

“Time will tell how this law will impact admission review policies and decisions as well as alumni engagement,” Smith said.