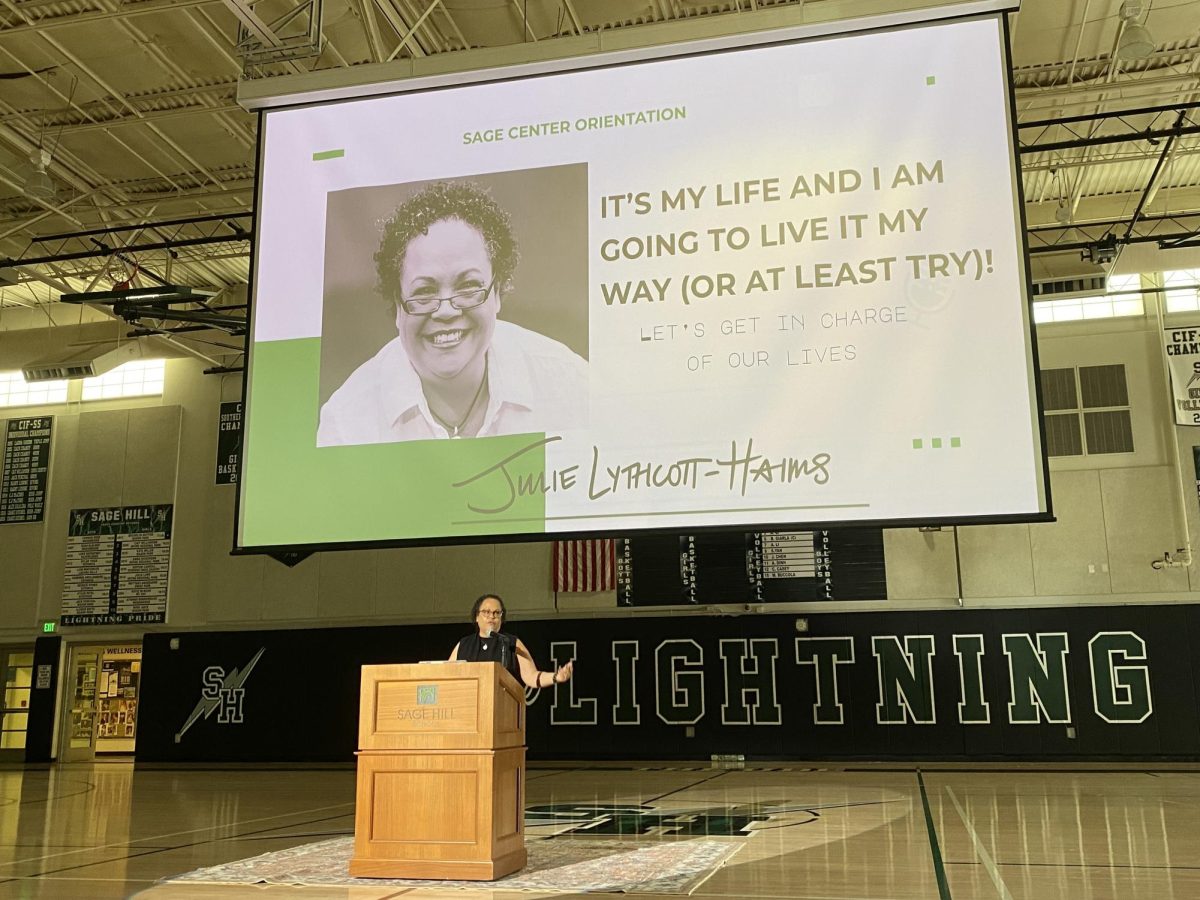

On Sept. 27, bestselling author and former Stanford University freshman dean Julie Lythcott-Haims spoke to the school community about how to be and raise adults, topics which are discussed in her books “Your Turn” and “How to Raise an Adult.”

Her visit to Sage Hill was divided into two parts: a morning talk in the Peter V. Ueberroth Gym where Lythcott-Haims spoke to all students and an evening event largely attended by parents in the Kazu Fukuda Black Box Theater. She advised students to study what they love, not what would please others, and she advised parents to avoid micromanaging or overparenting because doing so stunts the development of agency and resilience in their children.

“Without agency and resilience, a person is more likely to have anxiety and depression and to have less executive function,” Lythcott-Haims said.

Her morning talk was catered to students. Lythcott-Haims spoke about the misery that awaits those who are forced by external pressures to pursue something they are not passionate about. Her anecdotes came from her experience advising students at Stanford University and her own personal experience of starting a career in corporate law because the trade was deemed praiseworthy by society.

“But winning their approval, which I was, had me crying on my back porch because I was so desperately unhappy with the work that I was doing,” Lythcott-Haims said.

She encouraged students not to go by their parents’ or society’s definition of success, but to follow their own passions instead. She left students with a few things to remember: that they inherently matter, they shouldn’t expect perfection, they should think and do for themselves, they should widen their mindset about higher education, they should study what they love, and they must treat others with the dignity and respect every human deserves, which is the essence of good character.

To wrap up the talk, Lythcott-Haims recognized that parents, including herself, sometimes overstep their boundaries and micromanage the lives of their children, making it much more difficult for their children to follow their passions. To that end, she invited students to encourage their parents to come to her second talk later that night.

Lythcott-Haims began her evening discussion with the parents by defining three different types of overparenting: overprotective, fiercely directive, and helpful to the point of undermining. She spoke to the parents about her time working at Stanford University and described just how mentally unwell and ill-equipped overparented students were.

In her talk, Lythcott-Haims admitted to and described her mistakes as a parent of her two children, Sawyer and Avery, how it affected them, how she realized her missteps, and how she grew as a mother and as a person by rectifying these unhealthy parental behaviors.

Lythcott-Haims then offered parents some advice on how to better prepare their children for the life ahead of them by avoiding overparenting, saying, “Our job as parents is actually to put ourselves out of the job. Meaning, our kids can one day be okay without us.”

To do this, she insisted that parents show the same amount of love to their children regardless of their grades or test scores, ignore the arbitrary college rankings, teach their children how to live instead of living for them, and stop hounding their children about their academic performance.

“Don’t make your life about controlling your kids’ life. When you get a life, your kid can get one too,” Lythcott-Haims said.

During a question and answer session, a handful of parents in the audience admitted to making the same mistakes and asked her for advice on how to change.

“Neither of my kids is doing remotely what I wanted them to do, and I have never been prouder of Avery and Sawyer. I also think they’re proud of me for how I’ve grown and changed to love and accept and support them as they are,” Lythcott-Haims said.