Commentary: Inflated Grades, Inflated Egos, Inflated Futures

In an effort to accurately report the many viewpoints surrounding this issue, I interviewed six teachers from the math, world languages and science departments as well as the Dean of Faculty and Curriculum. I also sent out a survey to the faculty, to which 19 teachers responded from every department except PE. The quotes in this article are from these interviews and responses to the survey. Many teachers and students requested to remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of this article.

May 11, 2018

Did you get all As last semester? If so, you’re not alone.

Rumors of grade inflation have long circulated the halls of Sage, but now teachers are confirming an issue that the administration says doesn’t exist.

Here’s what I know. Three teachers confirmed to me that in a compiled list of 2017-2018 first semester grades, roughly 70-75 percent of all grades were As or A-s. Over 50 percent were As. And there were zero Ds, zero Fs and fewer than ten Cs awarded (I asked administration to see these lists of compiled grades, or comparable lists of anonymous grades stripped of teacher and course identification, but was denied access).

To put this in perspective, there are currently 538 students enrolled at Sage. If we approximate that each student is taking 6 classes, then less than 10/3228, or 0.31 percent, of all grades were Cs last semester (if you round up). All other grades, or 99.7 percent of grades, were above a C.

However, Matt Balossi, Dean of Faculty and Curriculum, rejected that there is any grade inflation at Sage.

“Grade inflation is a very different thing than grades trending higher,” Balossi said. “Grades can trend higher because kids deserve the higher grade. That doesn’t necessarily mean that their grades are inflated.”

Balossi argued that Sage has created an environment that is conducive to high achievement, hence the overwhelming amount of high grades.

“If you have smart, diligent, hardworking students and dedicated, professional, well-equipped teachers, then we should expect our students to be doing really well and their grades to reflect that,” Balossi said.

Several teachers I talked to disagree with this perspective.

“The student attitude toward learning helps a lot, and all these [avenues] of support that the community has built in helps,” said one teacher. “But, that doesn’t explain the extent to which we have this skewed distribution towards As. And it’s heavily skewed toward A-s and As.”

In the words of another teacher, “There’s no question there’s grade inflation at Sage, but that is not the official party line.”

This conviction was overwhelmingly echoed in a survey that The Bolt sent to teachers last week. In response to the question, “Have you noticed any grade inflation at Sage? (Where ‘grade inflation’ is defined as the tendency to progressively award higher grades for work that would have previously earned a lower grade),” 17 of 19 teachers responded “Yes” and two responded “I’m not sure … I haven’t been teaching at Sage long enough to assess this.”

——

During the first half of its existence, Sage earned a reputation as a school of great academic rigor.

According to one long-time teacher, it was common knowledge that students could attend Sage and have a valuable, in-depth learning experience but might earn a lower GPA than their counterparts at local public schools due to this rigor. As a result, the school tended to attract those with learning, instead of college or grades, as their primary academic goal.

For example, in a class of 12 to 15 students, normally one or two students would have an A, a couple of others would have an A- and the majority would have Bs. “An A was much more special back then,” said one teacher. “It’s lost its specialness.”

Then, the economic crisis of 2008 and 2009 occurred. Several teachers cite this as a major catalyst for grade inflation. Some faculty members were let go, and enrollment diminished.

As a business, the school was forced to reevaluate what could be improved and marketed to attract more customers. According to several teachers I talked to, the school’s solution seemed to be to inflate grades. This made Sage a more appealing educational provider by eliminating some families’ fear that their student’s GPA would suffer at Sage.

Teachers were asked to include categories of assessment that allowed more students to score higher grades. For instance, participation and effort grades were added, resulting in higher average grades because “everyone has the ability to participate and show good effort.”

One teacher told me that this was “not unethical grade inflation” and that it even came with its benefits. For example, participation grades that were intended to increase grade averages also encouraged quiet students to be more vocal during class.

Effort and participation remain a staple in the Sage teacher’s grading rubric.

—–

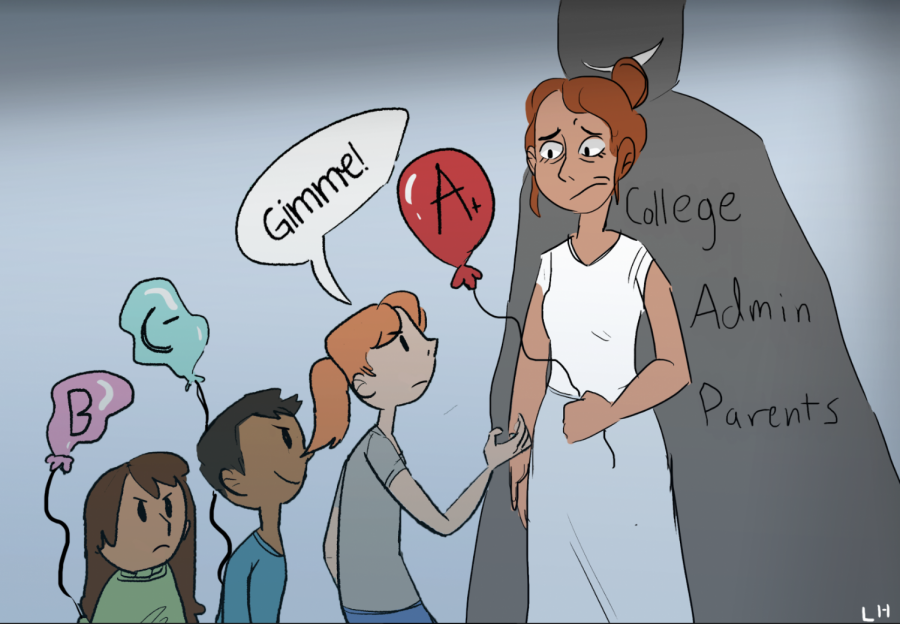

Other pressures have emerged, as well. An intense combination of parental, student, administrative and college pressure have put teachers in a tough spot.

When students don’t get the grade they want, they may “grade grub” or their parents may take initiative by pressuring teachers directly or indirectly via the administration.

“It’s easier to give As than it is not. It’s just always been the case that you don’t have fights from both the administration and parents,” one teacher told me.

Particularly in the context of college admissions, the same teacher said, “Parents know [their students] have to be above average, so, they work really hard to do that. They fight tooth and nail and bitch and moan if they don’t get [the higher grade], even if it’s clearly the student’s problem.”

Every year parents and students try to get grades above the average of their class. Yet each year that average is raised.

“As people get the higher grades, they start expecting the higher grades,” this teacher said.

Another teacher shared that, “Parents and students are demanding higher grades due to both real pressures from college admissions, and a perceived sense of entitlement, both of which are antithetical to a genuinely high-quality education.”

“Teachers should feel empowered and supported in their assessments,” this teacher continued. “When grades are inflated, or changed due to parent pressure, it devalues the learning process and undercuts a teacher’s training and expertise.”

There’s also a sense that teachers’ grades must fall within an acceptable range. “You get judged on how your grades looked compared to everyone else. You can’t be too far out of line,” a teacher said. This is not an inherently bad practice, but “if everybody else is giving easier grades because it’s easier, then [you have to follow in suit].”

One teacher gave insight into the administration-teacher dynamic. “I don’t feel direct pressure, but I think we have indirect pressure.” That is, there is no explicit instruction to award high grades. However, teachers know that if their grade averages are on the lower end, meetings, justifications and “a whole lot of headaches” will likely ensue. “So, indirectly, you know, well if I give only As and Bs (and not too many Cs), then you can fly under the radar,” this teacher added.

But are students working harder than they have in the past? Could a better work ethic be the cause of these grade trends? The teachers I talked to said no. Although students seem busier and more “overscheduled” than in the past, they do not seem to be working any harder. Instead, their time is divided between more activities and their learning is less concentrated.

An emerging pattern is that students have a sense of entitlement over the grade they think they deserve. “There’s almost an expectation that for a certain degree of effort, they should be getting an A,” said one teacher.

As David Pulitzer, a science teacher who joined Sage this school year, observed, “There’s definitely more of a focus on grade outcomes as opposed to learning outcomes than I anticipated. When I came here, it seemed to be ‘I want the grade before the process.’” He has worked to change this student mentality, instead advocating that students engage with and learn to enjoy the material. When you appreciate the learning process, “the grade follows.”

—-

So, what are the ramifications of all this?

Multiple teachers are concerned that the system is doing students a disservice by awarding grades that do not reflect a true mastery of a given subject. According to one teacher, the biggest ramification of grade inflation is that students develop a “completely altered and skewed sense of self.” As another teacher said, “There’s a lot to be learned from an honest grade.”

Additionally, extremely high GPAs are no longer unique and may no longer be indicative of high-quality work.

A sentiment I heard repeated over and over among faculty is that, “There’s no differentiating students when everybody’s GPAs are all clustered together.”

“While it may be particularly egregious here, grade inflation is not exclusive to Sage,” said English teacher Christopher Hathaway. “There are many high-achieving institutions (Harvard, for instance, is notorious for its inflated averages) that suffer in this way. The consequence of all of this is a narrowing of the gap between those who are talented and putting in an honest effort and those who aren’t. It’s catering to the bottom half of the student population, which must be frustrating for those kids who work hard because they’re genuinely interested in learning.”

“We are not trying to fit our students to a more even distribution of grades,” said science teacher Todd Haney. “We want all of our students to achieve high marks across the board. The issue at hand is whether or not the grades we award represent honest, accurate measures of each student’s understanding.”

Several students I talked to have also noticed unbalanced grading.

“People like to get their satisfaction from grades instead of actually getting a good grasp on the material,” observed one senior boy. “I think we’re definitely not the only ones that have it, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that maybe some students don’t necessarily get the grades that they deserve in class.”

Taylor Garcia, another senior, reflected on her own grade progression. “In the last couple of years, I feel like I haven’t been working as hard, and my grades don’t really reflect that. It’s kind of an odd disconnect.”

Some faculty are hopeful of the direction Sage has recently taken.

“In fairness, we’re spending much more time on this now, and the faculty does have discussions about this sort of thing behind closed doors, whether that’s as a whole faculty or in subgroups within departments,” said Haney. “But the fact of the matter is that one of the issues the school probably needs to address is how this is treated from department to department, or even from person to person within a department.”

Others are wary. The fact that so many faculty would only go on-record for this article if they could remain anonymous indicates the tension and lack of openness surrounding this topic. A major sentiment among the faculty can be summed up by one teacher’s observation: “It’s a big, pink, white elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about.”

—–

If there’s anything I’ve found while researching grade inflation, it is that this problem is indicative of larger issues facing not only our community, but communities nationwide. It’s students’ progressive disinterest in learning and concern with gaming the system. It’s excessive parental pressure and interference. It’s overstretched students. It’s the college process on steroids.

The bottom line is this. Higher grades result in more satisfied students, happier parents and a less jostled administration. Yet at the end of the day, grades are only a letter, a number. The knowledge gained through learning is what sustains personal development, career achievement and community advancement.